Embracing Change

Fighting for High Standards

Training Up!

At the founding of the Brotherhood of Carpenters union in 1881, delegates passed resolutions on their most pressing issues. They first centered on advocating for shorter hours of work, “in order that labor-saving machinery may not be so extensively employed in reducing the compensation due to skilled labor.”

The resolution was a commitment to fight for better wages, hours and working conditions for carpenters, to improve the quality of their lives. But it was also a response to the pace of change within construction, where industrial production with woodworking machinery was allowing large, mechanized planing mills to produce items like window frames, moldings and door sashes for the first time.

Technological change was disturbing for individual carpenters, who had always produced these products by hand, at the worksite. Now they faced lost hours and unsteady work.

Founding General Secretary Peter J. McGuire wrote about the problem in his first issue of The Carpenter. He was concerned about the rise of piecework and what that would do to drive down skill levels. To McGuire, this added to “the evils” developing in the trade:

“The entire absence of any apprentice system, or of any method of mechanical training, contributed to augment the evils,” McGuire wrote.

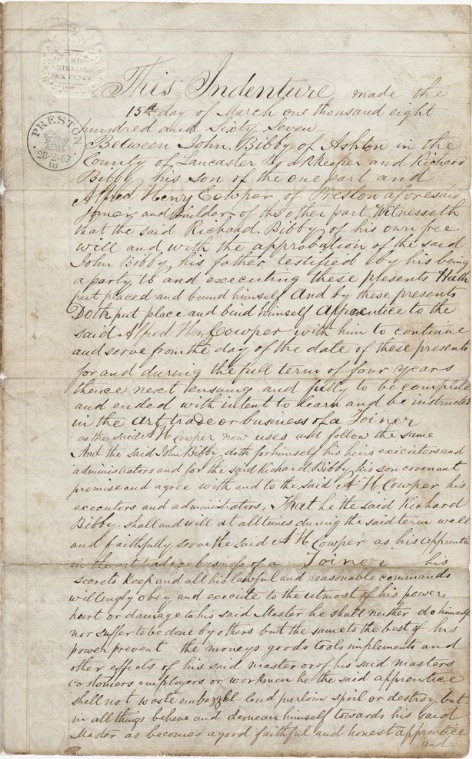

McGuire favored creating a union-regulated apprentice system for carpenters as a way to uphold high standards for workers and strengthen the union’s ability to protect members against the constant turmoil caused by rapid technological change.

During the first decade of the UBC’s existence, training and apprenticeship were constantly under discussion, but it was difficult to establish standards that would work in every area. In 1912, the convention passed an advisory resolution setting a four-year apprenticeship initiated between the ages of 17 and 22, with numbers and wage levels set by district councils.

For example, New York locals allowed one apprentice for every 10 journey-level carpenters. In Pittsburgh, anyone under age 25 could enter an apprenticeship. Ratios were higher in the less-developed West due to the scarcity of skilled labor, including in San Francisco, where as many as 10 apprentices could enter for every 48 journeypersons.

Chicago’s system was seen as a national model, based on an agreement between the district council and the contractors’ association. It required apprentices to attend courses during the winter, with pay.

Apprenticeship regulations continued to be set at the district level, but convention delegates and UBC leaders worked to establish broad minimum standards. From the time the U.S. Department of Labor established the Bureau of Apprenticeship Training in 1937, the UBC cooperated with its initiatives.

In 1946 the UBC created a standing committee on apprenticeship and developed a standard training manual that was widely used throughout the U.S. and Canada.

For 20 years starting in 1945, the UBC successfully trained 30,000 to 40,000 apprentices annually. In 1966 the union established its Apprenticeship and Training Department—and was recognized by the U.S. government, which granted the UBC a Manpower Development Training Act contract to develop a program for disadvantaged and minority youth. The UBC’s Job Corps program has operated since that time and trained tens of thousands of young people.

Apprenticeship continues as the centerpiece of UBC craft training, but today’s member knows that building skills is a career-long necessity. The pace of technological change is faster than ever, and employers demand qualifications and certifications in an increasing number of specialties. Scores of journey-level upgrade programs and craft-specific programs are offered at regional training centers across the U.S. and Canada.

The UBC’s early convention delegates recognized the connection between well-trained carpenters, better pay and conditions and a stronger union. That principle continues to drive our work today.

Sources:

The Road to Dignity: A Century of Conflict by Thomas Brooks

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters: The First Hundred Years, by Walter Galenson

With Our Hands: The Story of Carpenters in Massachusetts, by Mark Erlich